Monte Carlo Subsurface Scattering

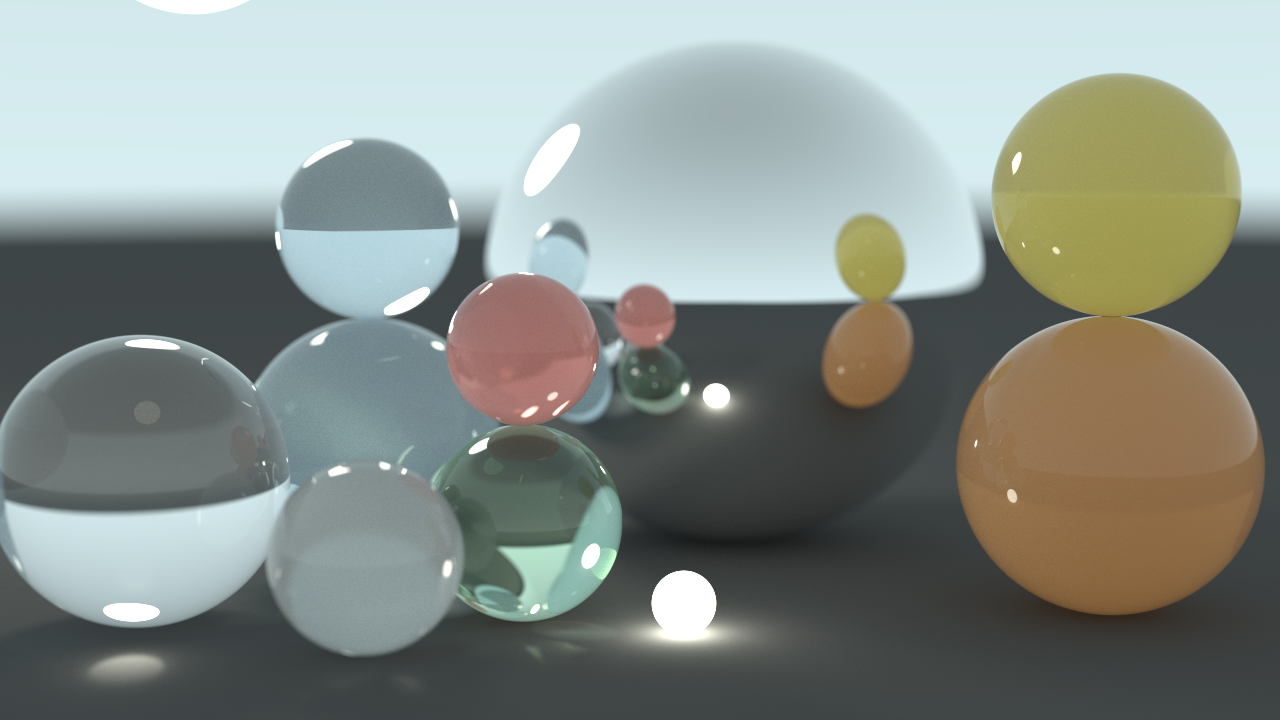

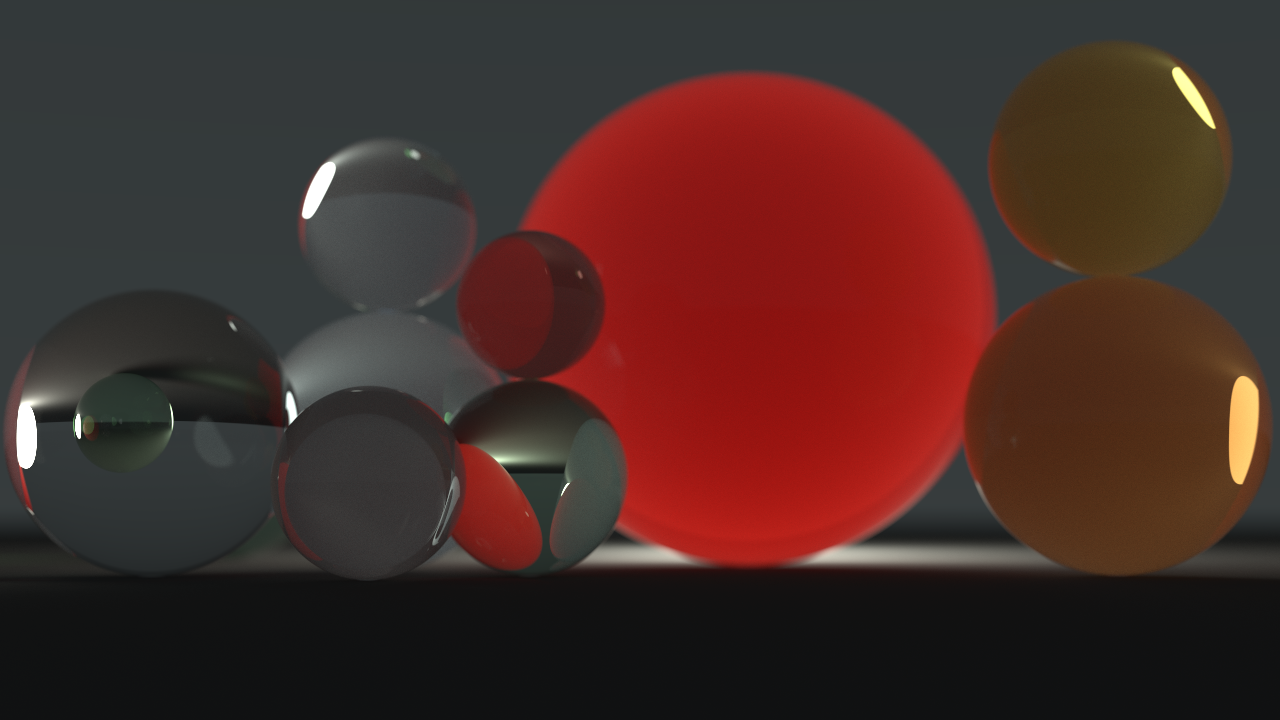

The renderer now features isotropic Monte Carlo subsurface scattering. The implementation is not limited to subsurface scattering but works as a general volumetric participating media system. To show it in images by rendering smoke or something similar would require more 3D modelling however.

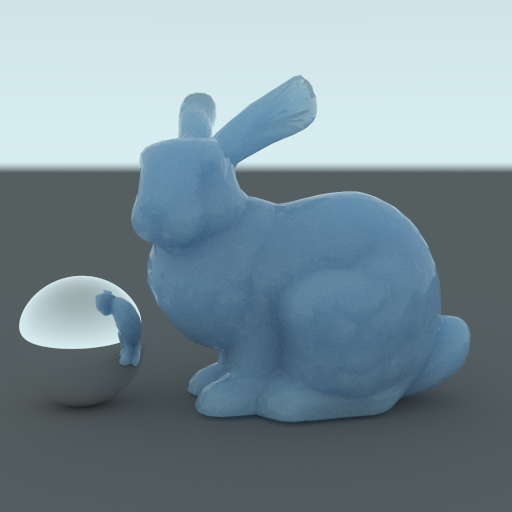

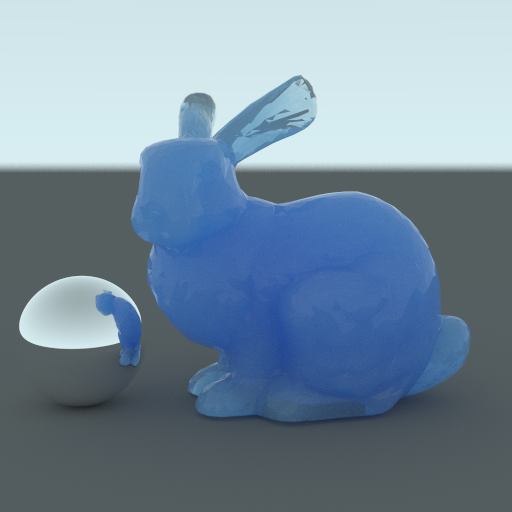

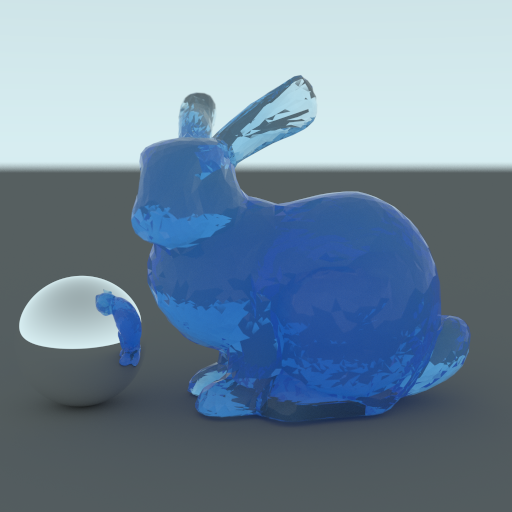

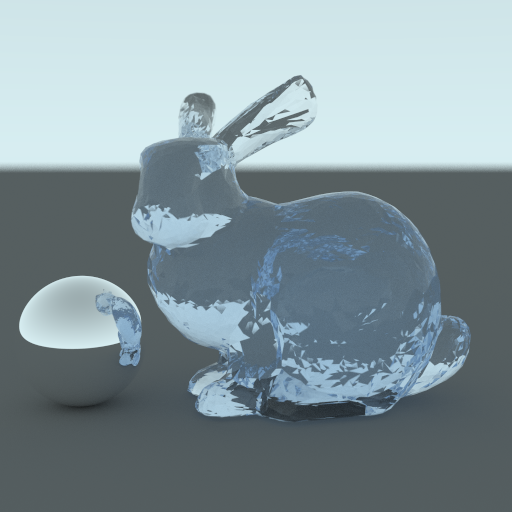

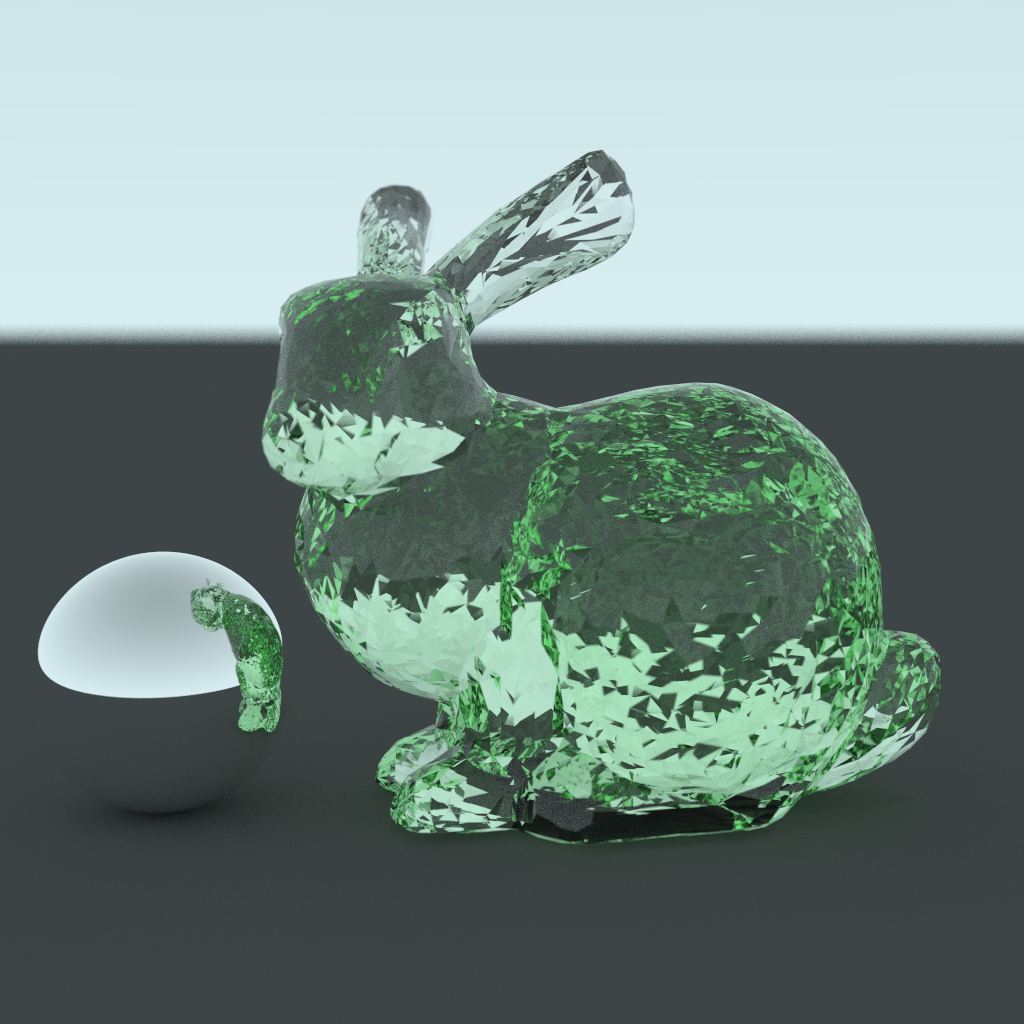

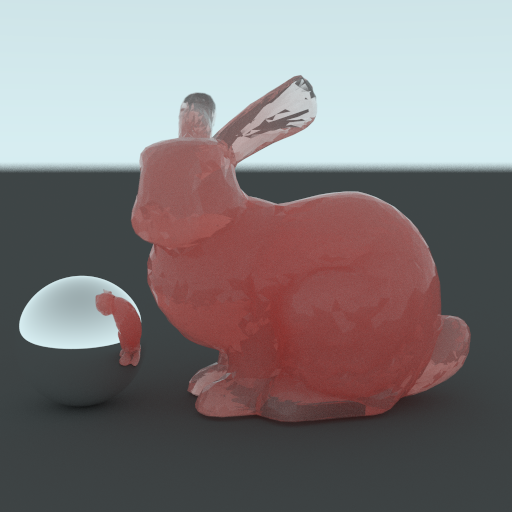

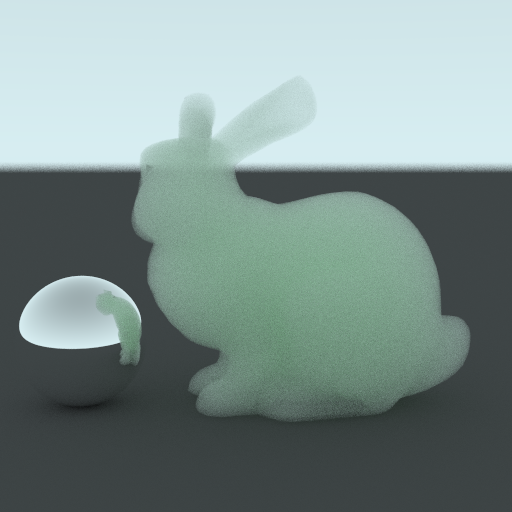

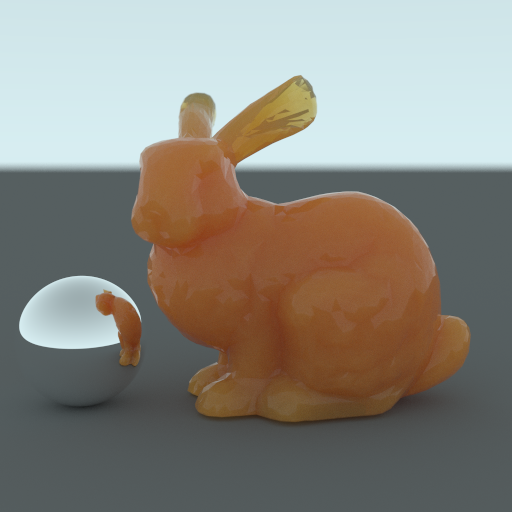

The implementation uses the reduced scattering coefficient and the absorption coefficient to sample a scattering distance and direction and compute the absorption. A higher scattering coefficient results in less transparency in the material, and the color of the material is determined by the absorption. Below are 4 renderings of the Stanford bunny at reduced scattering coefficients of 64, 16, 4 and 1, respectively. In the rightmost picture, the absorption coefficient has been reduced as well, giving off the appearance of blue-tinted glass. Notice also how the material appears clearer in areas such as the ears and tail where the model is not as thick.

The material absorption is computed using the Beer-Lambert law. When the scattering coefficient is high, the distance traveled by the light is low which means that the transmission from the Beer-Lambert law is going to be higher for a given absorption coefficient. This is why the blue color appears darker and darker as the scattering coefficient is reduced, except in the case where the absorption coefficient has been reduced.

This method of computing volumetric scattering is brute-force and therefore takes a lot longer to converge than for ideally specular, transmissive and diffuse materials. When rendering these images I used a maximum number of ray bounces of 40, which means that it will take a long time for many rays before they terminate. This is necessary in order to capture the subsurface scattering phenomenon well, but means that the time spend per iteration is longer. The fact that I don’t have an acceleration structure in place yet makes things even worse, as I currently check for intersections with the over 4k triangles of the bunny model in a serial fashion. Nevertheless, when rendering images like this at a resolution of 512x512 pixels, the engine spends around half a second per iteration, which is fast enough to show some of the implemented rendering models if not quite fast enough for interactive use.

Below are some subsurface scattering pictures and more bunnies, including one where the index of refraction is set to be lower than that of air, resulting in 100% transmission rate and a smoke-like bunny.

This will be the last contribution to the renderer for this project, though I will continue developing it in my free time to learn more. Below is a list of some of the immediate system-related concerns I aim to fix in the renderer, as well as graphics features I would like to add incrementally.

- Parallel BVH construction/traversal

- Memory manager class for CUDA

- Separate ray tracing and BSDF evaluation into separate kernels

- Proper system for material modeling, very hardcoded at the moment

- Robust and flexible scene/mesh loading

- Replace legacy OpenGL calls with a modern implementation

- Wireframe/Lightweight rendering mode

- Dithering

- Microfacet modelling

- Anisotropic subsurface scattering

- Texture/Normal/Displacement/Environment mapping

- Bidirectional Path Tracing

- Metropolis Light Transport

- …